How Might the Gut-Skin Axis Affect HS?

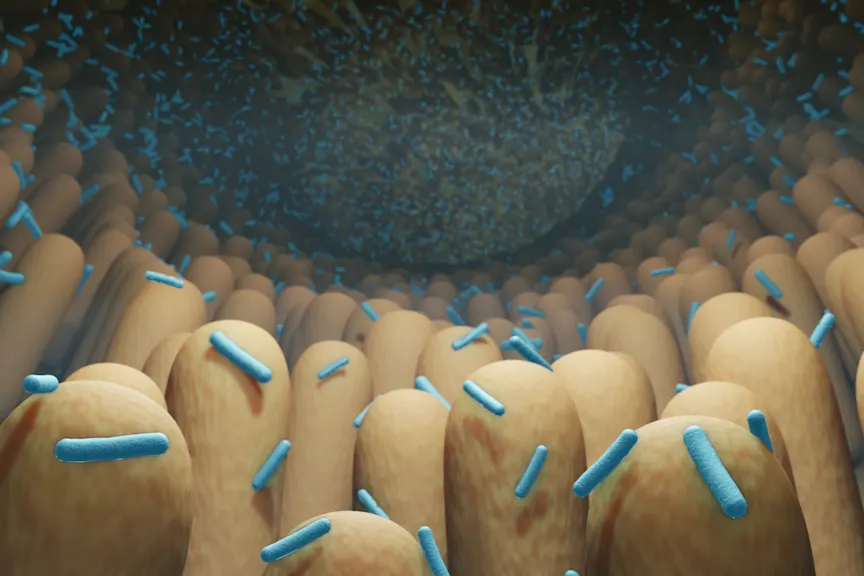

The trillions of bacteria found on our skin and inside our bellies (and how they interact) may hold the key to treating hidradenitis suppurativa.

For the pastdecade or so, researchers have been increasingly looking to bacteria—in our guts and on the surface of our skin—for clues about autoinflammatory conditions likehidradenitis suppurativa(HS), a chronic disease that produces painful, recurring cysts, boils, and abscesses.

It makes sense, when you think about it: Our immune system’s defenses are found in our intestinal and cutaneous (that’s skin to you and me) microbiomes, where trillions of harmless and disease-causing microbes (not just bacteria, but also viruses, fungi, and parasites) teem, duking it out to keep our bodies healthy.

But while the skin connection to HS almost seems obvious, since its symptoms surface near the groin, in the armpits, between the buttocks, or within the folds of the breasts, the gut connection may seem more mysterious. We looked to the research, and to two tophidradenitis suppurativaexperts, for answers.

A Possible Bacterial Imbalance

每个人的肠道菌群有不同类型的bacteria, a balance of beneficial (or neutral bacteria) co-existing with illness-causing microbes. But anything—an illness, an infection, even antibiotics—can knock that balance off-course, causing something calleddysbiosis, meaning there’s less diversity and more of the so-called “bad” bacteria left to wreak some havoc.

Dysbiosis may help explain what’s going on in the guts and on the of skin of people who have a chronic condition like HS. But there is also the interaction between the bacteria in your intestines and your skin—which scientists call thegut-skin axis—to consider. And this interplay may be pretty important.

“Gut-skin axis refers to the crosstalk between the microbiome of the skin and the microbiome of the gut, and the disease manifestations or conditions that can occur in relation to that,” explains Alexandra P. Charrow, M.D., director of the hidradenitis suppurativa and neutrophilic dermatosis clinic at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and instructor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School in Cambridge, MA.

There have been a number of studies looking at the gut microbiome of people with other inflammatory skin disorders likepsoriasisandeczema. In them, researchers found what Dr. Charrow calls significant dysbiosis. “So that would suggest that there's something about the gut and the microbiome they have in their gut, and their skin," she notes.

So what does it all mean for folks with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)? “The short answer is, we do not know,” admits Dr. Charrow—yet. Still, there are theories and clues, which may lead to better treatments, she adds.

Bacteria Is a Likely Factor in HS

Doctors know that bacteria are involved in hidradenitis suppurativa, buthowisn’t exactly clear.

“Our current understanding of HS is still pretty rudimentary,” notes Haley B. Naik, M.D., associate professor of clinical dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco. What doctors suspect could be happening is that the hair follicles in HS patients don’t work correctly, so the follicles form plugs. The plug’s contents—the bacteria and debris from cells—leads to the development of a cyst and then ruptures from the pressure, spreading deep inside the skin instead of on its surface. That bacteria, along with the rest of the materials in the hair follicle, produce an inflammatory response, explains Dr. Naik.

In mild cases of HS, that might mean a few painful boil-like nodules. In the more serious form of the disease, those nodules connect to form even more painful tunnels beneath the skin.

One clue that disease-causing bacteria are behind HS? When doctors swab the pus-filled lesions and nodules they find normal bacteria as well as staph aureus, the most dangerous of all the many common staphylococcal bacteria, according to Merck Manual. Another? Many, if not all, people with HS improve when they’re given antibiotics, whether topical or oral meds.

This evidence “suggests that there is some role of the bacteria in the disease’s development. But we don’t know exactly what is happening in that sort of relationship,” explains Dr. Charrow. It could be that you might have an overactive immune system that produces the inflammatory reaction to the bacteria on your skin. Or it could be that there’s some imbalance of bacteria that specifically reacts with your immune system. “Then, maybe there’s a third factor that’s involved. That might be somebody’s hair follicles, plus the bacteria, plus the person’s immune system, plus hormonal factors, all of which may be playing a role,” she notes.

细菌网络可能涉及

In the early days of studying the human microbiome, says Dr. Naik, “there was a thought that, ‘Oh, we just need to find the one bad actor. We need to find the one bad bug and once we can eradicate that bug, we can get rid of X condition.’” Instead, scientists now think that inside everyone’s gut are networks of bacteria working together to cause diseases or maintain health.

So if you have HS, you may have specific strains of bacteria acting together in your gut to produce protiens that trigger your immune system to go awry, Dr. Naik explains. “And that immune dysfunction leads to the inflammatory response that occurs when it’s coupled with somebody who’s predisposed to HS. That process is responsible for both the initial outbreak and the flares that keep recurring, she adds.

To date, there have been very few studies examining the gut flora in HS patients, specifically, and in the few that have been done researchers haven’t found much difference between HS patients and non-HS patients, explains Dr. Charrow. Researchers haven’t found much of an imbalance or lack of diversity, either. That doesn’t mean that it’s not there—at this point, no study has looked at the gut microbiome of people with severe HS, she notes.

Anaerobic Bacteria May Hold Some Answers

While the gut microbiome has yet to reveal its secrets, scientists have found that there are shifts in the type of bacteria on the skin of HS patients, both in the lesion-filled areas and those parts of the skin that don’t have any outbreaks.

One difference: There are fewer of the so-called “normal” skin bacteria (that everyone has) and more anaerobic bacteria, which are bacteria that don’t need (and prefer not to have) oxygen to survive, Dr. Naik explains. Typically, anaerobic bacteria don’t live on the skin’s surface, “so if anaerobic bacteria is there, why is it there?” she asks.

One theory: “Anaerobic bacteria could be driving inflammation in HS because in otherwise healthy people who don’t have HS, those bacteria don’t exist in abundance on the surface of the skin,” Dr. Naik points out. “The other theory is that they’re just secondary actors that don’t play a role in causing or driving HS but are the result of the primary process, whatever that might be.”

One drawback to this focus of research is that it hasn’t followed HS patients over the long term to see if the type of bacteria changes during flares and periods of remission, so these results are snapshots and small pieces in the larger puzzle as doctors figure out what’s happening in HS.

Better Treatments Are in Store

所有这些研究的希望和目标的直觉and skin is threefold, says Dr. Charrow. “One would be to be more targeted for patients in their treatment. Two would be to get a better understanding of the disease, in general. And three might be to categorize people,” she explains. For instance, if your HS takes the form of a blackhead-dominant condition, you may be growing bacteria that is different from the person with HS who has lesions that are oozing pus.

知道这些我们uld allow doctors to prescribe different types of antibiotics for each. Right now, all patients get broad-based antibiotics as a first-line treatment. But in the future, someone might get a more targeted topical cream or an injectable antibiotic.

That would be a godsend for people with HS. You can’t keep people on antibiotics for years (they have side effects and bacteria may become resistant), and aside from surgery and TNF-inhibitors (like Humira), those topical and oral meds are a mainstay.

“If it’s the gut microbiome that we ultimately end up targeting, maybe we would be thinking about fecal transplants or about specific diets,” Dr. Charrow says. “I think the sky’s the limit with HS, because there’s so much we still don’t understand.”

Gut Microbiome and Disease:Journal of Experimental Medicine. (2019.) “The gut microbiome: Relationships with disease and opportunities for therapy.”https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6314516/

Skin Microbiome in HS:International Journal of Molecular Science. (2020.) “The Role of the Cutaneous Microbiome in Hidradenitis Suppurativa—Light at the End of the Microbiological Tunnel.”https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7072827/

Gut Microbiome in HS:Journal of Investigative Dermatology. (2021.) “Altered Skin and Gut Microbiome in Hidradenitis Suppurativa.”https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0022202X21016572